|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To change the background color for a terminal session using the PuTTY ssh and telnet program, take the following steps:

The

Secure Shell (SSH) protocol provides a means one can use for

secure, encrypted connections between systems for logins or file transfers.

One can use a username and password to login from an SSH client to an SSH

server or one can use a

public and private key combination where a public

key for a user's account is stored on a remote SSH server while a corresponding

private key is stored on the system from which the user will initiate the

SSH or SFTP connection. On

Linux systems,

private keys are normally stored in the .ssh directory

beneath the home directory for your account. If you haven't created

any keys yet, the directory may only contain a known_hosts

file that contains public keys for servers you've previously logged into

via SSH.

[ More Info ]

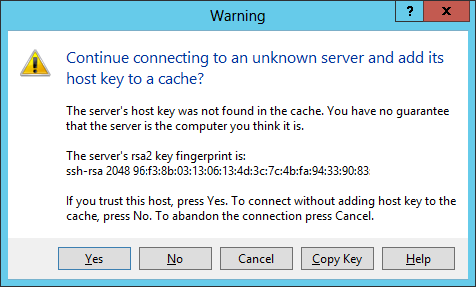

$ ssh-keygen -l -f /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key.pub 2048 96:f3:8b:03:13:06:13:4d:3c:7c:4b:fa:94:33:90:83 (RSA) $

The -l option shows the fingerprint of a specified public key file.

Private RSA1 keys are also supported. For

RSA

and DSA keys, ssh-keygen tries to find the matching public key

file and prints its fingerprint. If the -l option is combined

with -v, an ASCII art representation of the key is supplied with

the fingerprint. The -f filename option allows you to

specify the file name of the key file.

The ssh-keygen -l -f /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key.pub command isn't

showing the key itself, but instead shows the

"fingerprint" for

the key, which is a sequence of 32

hexadecimal

digits. You can see the much larger key value itself by issuing the

command cat /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key.pub.

Received too large (1298752370 B) SFTP package. Max supported package size

is 1024000 B.

The error is typically caused by message printed from startup script (like

.profile). The message may start with "Micr".

Cannot initialize SFTP protocol. Is the host running a SFTP server?

[ More Info ]

$ ssh jdoe@example.com

But, if you just were logging in to enter one command, say you wanted

to find the hardware platform of the remote system using the

uname

command uname --hardware-platform, you could simply append that

command to the end of the above ssh command you would have used to log into

the remote system. E.g.:

$ ssh jdoe@example.com uname --hardware-platform jdoe@example.com's password: x86_64 $ uname --hardware-platform i386

In the example above, issuing the same command on the local system, i.e., the one on which the SSH command is being issued shows that the result returned when the uname command was issued at the end of the ssh command line returned a result from the remote system.

You may even be able to use a text-based editor, such as the vi editor, though you may see error messages like the ones below:

$ ssh jdoe@example.com vi temp.txt jdoe@example.com's password: Vim: Warning: Output is not to a terminal Vim: Warning: Input is not from a terminal

When you enter an ssh command in the form ssh

user@host the remote system allocates a

pseudo-tty (PTY), a

software abstraction used to handle keyboard input and screen

output. However, if you request SSH to run a command on the remote

server by appending that command after ssh user@host, then

no interactive terminal session is required and a PTY is not allocated, so

you see the error messages when you use a screen-based program intended for

use with a terminal, such as the vi editor.

For such cases you should inclde the -t option to the SSH

command.

| -t | Force pseudo-tty allocation. This can be used to execute arbitrary screen-based programs on a remote machine, which can be very useful, e.g. when implementing menu services. Multiple -t options force tty allocation, even if ssh has no local tty. |

E.g.:

$ ssh jdoe@example.com -t vi temp.txt

But there is an escape sequence that will allow me to terminate the current SSH session. Hitting the three keys listed below will allow me to terminate the session.

↲ Enter, ~, .

[ More Info ]

-o option with ServerAliveInterval

. You can specify the interval in seconds which will be used by the SSH

client to send

keepalive packets with -o ServerAliveInterval x

where x is the frequency for sending the keepalive packets. E.g.,

if I wanted the SSH client to send keepalive packets every minute (60 seconds)

to the remote SSH server, I could use a command like the one below when

establishing the SSH session:

$ ssh -o ServerAliveInterval=60 jdoe@example.com

By using this option, you should be able to reduce the likelihood that your SSH connection will get dropped after a certain amount of time due to no activity for the session.

You can also use the

ServerAliveCountMax

parameter with ServerAliveInterval to drop the connection, if the SSH

client hasn't received a response from the server to the prior "heartbeat"

signal when the time comes to send another keepalive packet. E.g., ssh

-o ServerAliveInterval=60 -o ServerAliveCountMax=1 jdoe@example.com

would result in the connection being dropped if the client was awaiting

a response to even one outstanding keepalive packet.

There is also a TCPKeepAlive option in

OpenSSH.

That option is used to recognize when a connection is no longer active due

to some problem such as the SSH client application crashing or a prolonged

network outage. If the SSH server never recognizes that the client is no

longer communicating with it, it will continue to allocate resources,

such as memory, for the connection. The option is turned on by default

in the OpenSSH configuration file /etc/ssh/sshd_config. You

will see the following line in that file:

#TCPKeepAlive yes

You don't need to uncomment the line by removing the pound sign, since "yes" is the default value. The option causes Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) to periodically transmit keepalive messages. If it doesn't receive responses within the expected time, it returns an error to the sshd process, which will then shut down the connection. The purpose of this option is to prevent half-dead connections building up over time and consuming more and more system resources as the number grows. The keepalive interval is typically in the order of hours rather than minutes to minimize the network load for the server. If the keepalive period was made shorter, that would affect all TCP connections on the system, not just the SSH ones, potentially increasing the network load unnecessarily and also causing connections to be dropped even for transient issues, such as a short and temporary network issue.

The TCPKeepalive option is for dealing with longer term issues for a connection rather than the loss of connectivity due to firewall, proxying, or Network Address Translation (NAT) timeouts. You can specify the option on the command line at the SSH client end as follows:

$ ssh -o TCPKeepAlive=yes joe@example.com

References:

The vulnerability resides only in the version end users use to connect to servers and not in versions used by servers. A maliciously configured server could exploit it to obtain the contents of the connecting computer's memory, including the private encryption key used for SSH connections. The bug is the result of code that enables an experimental roaming feature in OpenSSH versions 5.4 to 7.1

"The matching server code has never been shipped, but the client code was enabled by default and could be tricked by a malicious server into leaking client memory to the server, including private client user keys," OpenSSH officials wrote in an advisory published Thursday. "The authentication of the server host key prevents exploitation by a man-in-the-middle, so this information leak is restricted to connections to malicious or compromised servers."

The roaming feature was intended to allow users to resume broken SSH connections, even though the feature was disabled in OpenSSH server software years ago. E.g., when I connected to a server I have running OpenSSH server software, I saw the folowing:

$ ssh -v jdoe@127.0.0.1 2>&1 >/dev/null | grep -i 'roaming' debug1: Roaming not allowed by server

The Red Hat article on the vulnerability OpenSSH: Information-leak vulnerability (CVE-2016-0777) notes:

Since version 5.4, the OpenSSH client supports an undocumented feature called roaming. If a connection to an SSH server breaks unexpectedly, and if the SSH server supports roaming as well, the client is able to reconnect to the server and resume the interrupted SSH session. The roaming feature is enabled by default in OpenSSH clients, even though no OpenSSH server version implements the roaming feature.

For affected products, the article also notes:

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 since version 7.1 has provided OpenSSH 6.6 for which the default configuration is not affected by this flaw. OpenSSH 6.6 is only vulnerable to this issue when used with certain non-default ProxyCommand settings. Security update RHSA-2016-0043 corrects this issue.

So CentOS 7 systems using a default OpenSSH configuration should be unaffected, since CentOS is derived from Red Hat Enterprise Linux.

On a Linux system, you can check the version of SSH installed with

ssh -V.

$ ssh -V OpenSSH_6.6.1p1, OpenSSL 1.0.1e-fips 11 Feb 2013

On a CentOS Linux system using the

RPM Package Manager

you can also use rpm -qi openssh | grep Version.

$ rpm -qi openssh | grep Version

Version : 6.6.1p1On a CentOS system, you can update the software from the command line, aka a

shell prompt, using the command yum update openssh.

If you are using a vulnerable OpenSSH client, you can also specify the

-oUseRoaming=no parameter on the command line to ensure that

a malicious server can't take advantage of the vulnerability. E.g.

ssh -oUseRoaming=no jdoe@example.com. Or the feature can

be disabled for all users on a system by putting UseRoaming no in

/etc/ssh/ssh_config or by an individual user for his account

by adding the line to ~/.ssh/config.

echo 'UseRoaming no' >> /etc/ssh/ssh_config

References:

I normally go through the process once a month from my MacBook Pro laptop running the OS X operating system when I need to place a monthly newsletter on the web server. I use an SSH command similar to the following to log into the bastion host where gold.example.com is the fully qualified domain name (FQDN) of the web server and bastion1.example.com is the bastion host.

ssh -L 22001:gold.example.com:22 jasmith1@bastion1.example.com

The -L option specifies I want to tunnel a local port on

my laptop, in this case I chose 22001, to port 22 on the web server,

gold.example.com. A tunnel is set up from my laptop to the web server

through the bastion host by using that option once my login is completed

to the bastion host.

Then, to transfer a file via secure copy from my laptop to the web server, I can use a command like the following one to transfer a file named July.txt from the laptop to the web server:

$ scp -P 22001 July.txt jasmith1@127.0.0.1:/data/htdocs/clubs/groot/newsletter/2015/. jasmith1@127.0.0.1's password:

The -P option to the scp command specifies I want to use

TCP

port 22001, since that is the port for the end of the tunnel on my laptop.

The 127.0.0.1 address I'm specifying is the

localhost, aka

"loopback", address on my laptop. I.e., I'm connecting to port 22001 on

the laptop itself. The tunnel I set up earlier results in any connection

to that port being forwared through the tunnel to the web server, so

I'm specifying my userid for the web server and the password prompt I

receive is for the web server. The file July.txt will thus be placed

in the directory /data/htdocs/clubs/groot/newsletter/2015

on the web server with the same name, July.txt.

If I wanted to pull a file from the webserver via the tunnel, I could use a command such as the following:

scp -P 22001 jasmith1@127.0.0.1:/data/htdocs/clubs/groot/July.html .

That command would retrieve the file July.html from the web server and place it on the laptop with the same name.